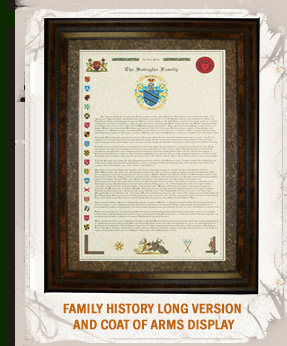

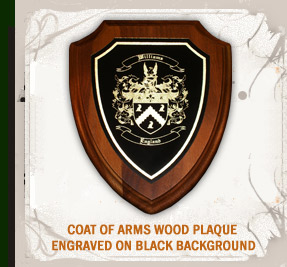

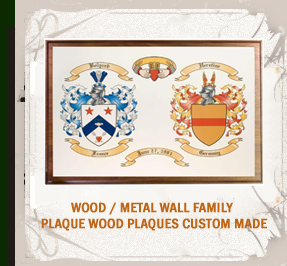

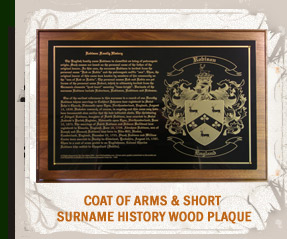

Display your Scottish coat of arms or your Scotland heritage

Early

Scottish History: Scotland is one of the oldest nations

of Western Europe. In its formation Gaels, Picts, Scots, Britons,

Anglo-Saxons, and Norsemen all took part. The Gaels belonged to

a branch of the Celtic peoples that reached Scotland from Central

Europe in the sixth century B.C. There they found the Picts, a people

of mysterious origin who may have come from the Continent as early

as 1000 B.C. The Gaels and Picts joined in defying the Romans when

these world conquerors began their invasion of northern Britain

about 80 A.D. Although the Romans succeeded in getting as far north

as the central lowlands, they never succeeded in subduing the fierce

barbarians, and early in the fifth century the Roman legions were

finally withdrawn. All of Britain then became the prey of new invaders

and new settlers.

The

first of the colonies in western Scotland was Dalriada, founded

early in the sixth century by Irish Celts called Scots in what is

now Argyll County. The kingdom of Strathclyde arose in the seventh

century, when Britons driven northward from England

by the invading Anglo-Saxons settled in the Clyde Valley. The Teutonic

migration reached southeastern Scotland in the sixth century, when

the Anglo-Saxons established Bernicia, later part of Thekingdom

of North-Ubria. Although the Gaels and Picts maintained their hold

over Pictavia, the Norsemen extended their control along the northern

coast and on the three outlying archipelagoes between the ninth

and eleventh centuries.

Scotland had

its first contact with Christianity early in the fifth century,

when the British missionary St. Ninian converted the southern Picts.

During the latter part of the sixth century the Irish missionary

which he had established on Iona in the Hebrides.

Scottish

Medieval Period: The first political union in Scotland

was achieved in 844, when Pictavia and Dalriada were united under

Kenneth MacAlpin as Kenneth I. The strong kingdom thus formed against

encroaching Norsemen and Anglo-Saxons was known as Alba until early

in the thirteenth century, when it was named Scotland. In 1018,

Malcolm II, after defeating the Anglo-Saxons, annexed the Lothian

district of Northumbria, thus extending the southern frontier of

Scotland to approximately its present limit. Most of the mainland

country was finally united in 1034, when Duncan I, King of Strathclyde,

succeeded Malcolm II, his maternal grandfather.

In 1040 his

general Macbeth killed Duncan, who despite Shakespeare's villainous

characterization, ruled competently until overthrown in 1057 by

Duncan's son, Malcolm III. Because of the influence of Malcolm's

English-born queen, Margaret, the central lowlands in particular

became an English-speaking region, with a culture modeled on that

of the Anglo-Saxons to the south. Early in the twelfth century Malcolm's

son, David I, not only introduced feudalism but developed a ruling

class whose interests differed greatly from those of the Celtic

masses of Scotland. Although some of the clan chieftains became

vassals, the majority of the King's liegemen were Anglo-Normans

who, in doing homage for their land, held most of the southern peasants

as serfs.

Finally, in

1174, when William the Lion of Scotland was captured on his invasion

of northern England, he was forced to sign the Treaty of Falaise,

whereby he not only became the vassal of Henry II but also placed

the entire Scottish Kingdom under the lordship of the English Crown.

The Scots did not regain their independence until 1189, when Richard

I of England sold them their freedom for funds with which to finance

the Third Crusade.

The consolidation

of Scotland was practically completed during the reign of Alexander

III, when the Scots defeated the Norsemen in 1263 and thus gained

control of the Hebrides and the coastal plain of the Highlands region.

But the Orkneys and Shetlands were not acquired until 1472, when

Norway transferred them to the Scottish Crown.

Scottish

War of Independence: Upon the mysterious death of the young

Norwegian Princess Margaret, granddaughter and heiress of Alexander

III, thirteen claimants to the throne appeared. The strongest were

John de Baliol and Robert de Bruce. Edward I of England arbitrated

the claim, and when he awarded the crown to Baliol in 1292, the

new monarch had to swear fealty to him. Four years later, goaded

into rebellion by Edward's oppressive measures against the

Scots, Baliol made an alliance with France.

In protest, the English invaded Scotland in 1296, and the massacre

of the citizens of Berwick was the prelude to a ruthless war that

resulted in Baliol's abdication.

Although Scotland

was now under an English military government, Sir William Wallace,

who won one of the greatest victories in Scottish history at the

Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297, renewed the popular revolt. A

year later, however, the Scots were defeated at Falkirk, and Wallace

was eventually betrayed to the English and executed in 1305. In

1306, Robert Bruce, grandson of the original candidate for the Scottish

throne, was crowned as Robert I. After seven years of guerrilla

warfare Bruce routed Edward II's army at the Battle of Bannockburn

in 1314.

In 1333, during

the reign of Bruce's son, the incompetent Daved II, English

forces scored a great victory at Halidon Hill and made Edward de

Baliol their vassal king. Baliol ceded almost half of the southern

uplands to England's Edward III, and it was not until 127

years later, during the reign of James II, that the Scots finally

expelled the English from the southeastern counties.

Rise

of the House of Stuart: The death of the childless David

II in 1371 brought the first of the Stuart dynasty to the Scottish

throne - Robert II. The ablest of his successors was James

I, who for about eighteen years was a prisoner of England's

Henry IV and Henry V. When finally released and crowned in 1424,

James initiated reforms that to a certain extent curbed the power

of the feudal lords, and brought about commercial, agricultural,

and legal improvements. He also established a two-chamber Parliament

similar to that of England, but retained the Council of the Lords

of the Articles to function between sessions.

Scotland took

part in England's Wars of the Roses on the side of the House

of Lancaster and recognized the claim of Perkin Warbeck, who attempted

to oust the Tudor King Henry VII. In 1497, however, James IV concluded

a truce with England and six years later he obtained English recognition

of an independent Scottish crown by marrying Henry's daughter

Margaret. Although this "union of the thistle and the rose"

led a century later to the union of the Scottish and English crowns,

it did not prevent the outbreak of hostilities when Scotland once

again allied itself with France. After Henry VIII went to war with

France, James invaded northern England and was defeated and slain

in the Battle of Flodden Field in 1513.

James V tried

to improve the lot of the common Scottish people when he assumed

control in 1528. He also protected the Roman Catholic Church, refusing

to follow the example of his uncle Henry VIII in severing all ties

with the Papacy and founding a national church like the Church of

England. The Scottish alliance with France was strengthened through

the King's two marriages, the first to a daughter of Francis

I, and the second to Mary of Guise.

The child of

James's second marriage was the ill-fated Mary Stuart, who

became queen one week after the English had defeated her father

in the Battle of Solway Moss in 1542. her reign was a particularly

turbulent one because of the attempt of her Catholic followers to

place her on the English throne, which the Protestant-supported

Elizabeth I ascended in 1558. The story of her unfortunate marriages,

of her forced abdication in favor of her infant son, and of the

nineteen years she spent in English prisons before her execution

is told in her biography {Mary Queen of Scots}.

During the regency

of Mary of Guise, the short reign of Mary, Queen of Scots, and the

minority of James VI the Reformation gained momentum in Scotland.

John Knox let this Reformation. He had been influenced during his

exile on the Continent by the teachings of John Calvin. In 1560

Knox drew p a Confession of Faith that paved the way for the establishment

of the church government and doctrine known as Presbyterianism.

Union

of Scotland and England: Mary's ambitions were fulfilled

in her son, who acceded to the English throne as James I on Elizabeth's

death in 1603. In his attempt to establish a uniform church government

in both Scotland and England, James initiated the long struggle

between the Church and the Crown that was carried on by all of his

Stuart successors. His object was to substitute the episcopacy {government

by bishops appointed by the king} for the presbytery {government

by democratic assemblies of ministers and elders}. The struggle

reached its height under Charles I, who, with thee aid of Archbishop

Laud, continued to impose the rites of the Anglican Church despite

the signing of the National Covenant, by which the Scottish Presbyterians

pledged defense of their faith.

The indecisive

Bishops' Wars of 1639-1640 were followed by the English Civil

War between the King and the Puritan-dominated Parliament. In the

Civil War the Scots sided with the Puritans, helping Cromwell to

win the Battle of Marston Moor in 1644, but five years later, outraged

by the execution of Charles I, they defied the Commonwealth by recognizing

his son, Charles II. After Charles II had been restored to the English

throne in 1660, Charles broke faith with the Scots in regard to

his promise of Liberty of conscience, and the Covenanters'

uprisings, which followed in the wake of Restoration attempts to

re-impose the episcopacy, continued until suppressed at the Battle

of Bothwell Bridge in 1679.

The Scots did

not achieve freedom from royal absolutism until the reign of William

III. The crowning of William and his wife Mary, a daughter of James

II, was accompanied in 1689 by the enactment of the Declaration

of Rights and the passage of the Act of Toleration, which restored

religious freedom to the realm. Finally, in 1707, five years after

Queen Anne came to the throne, both the Scottish and English Parliaments

accepted the treaty, which permanently united the two countries.

Thenceforth the history of Scotland was interwoven with that of

Great Britain, the hopes of the Stuarts for ousting Anne's

Hanoverian successors having twice come to no avail, in the Jacobite

uprising of 1715 and in the overthrow of the Young Pretender in

1746. The British union has had both economic and political advantages,

especially since the Scottish Reform Acts of 1832 and 1885 extended

the franchise and increased Scotland's representation in the

House of Commons.

Of course much

has changed since then and the nation of Scotland is a thriving

country proud of its heritage. Scotland is a place that you would

be proud to display your Scottish genealogy, family coat of arms

or surname history.