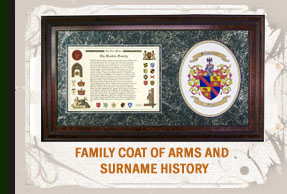

Display your German coat of arms or your Germany heritage

The

History of Early Germany and its Heritage: The origin of

the German people is unknown. However, as early as the time of Alexander

the Great, in the fourth century B.C., there is mention of German

tribes around the Baltic Sea, in what is now Scandinavia. Moving

southward and eastward, they reached the Rhine about 200 B.C. and

soon afterward pushed on into northeastern Gaul. In 102 -101

B.C. the tribe of the Teutones {Teutons} invaded Illyria, Gaul,

and Italy, but was defeated by the Roman general Marius. In his

Commentaries Julius Caesar tells of his encounters with certain

Germanic tribes in his Gallic Wars.

At various times

in Roman history the Romans were concerned with different German

tribes, and by the beginning of the Christian era, Roman dominion

had been firmly established in Germany. In 9 A.D., however, when

Emperor Augustus attempted to force Roman customs upon the German

people, they rebelled under the leadership of Arminius and completely

destroyed the Roman armies under General Varus. Never again did

the Romans establish themselves in Germany, and in the early centuries

of the Christina era they were often forced to defend themselves

against the invasion of powerful German tribes. It is interesting

to note that the Germans in reference to themselves did not use

the name Germani; the Romans from a Gallic word probably formed

it.

The roman historian

Tacitus, writing about A.D. 100, gives in his Germania a valuable

and interesting account of the customs and lives of the early Germans.

Although they were all of German blood, speaking a common language

and living under identical institutions, they were divided into

many tribes. The early tribal names mentioned by the Romans have

little historical significance; the better-known groupings of later

times were confederations of tribes, such as the Alemanni, Franks,

Vandals, Burgundians, Angles, Saxons, Lombards, and Goths. The Germans

lived in a land of fen and forest, dwelling in small villages of

wattled huts and practicing a rude form of agriculture. Most of

the people were free peasants, but above them was the class of nobles

and below ere the serfs and the slaves. A rudimentary form of representation

prevailed in the village council and in the county assembly and

court; in time of war the assembled tribesmen chose their military

chieftain. During the later years of the Roman Empire the tribes

bordering on the frontier became civilized and Christianized. To

a considerable degree these Germans also became romanized, learning

and adopting Roman building and farming methods and copying in many

instances the Roman way of life.

The

Wanderings of the German Nations: Late in the second century

A.D., furious warfare among the German tribes led to increasing

pressure on the Roman frontier. Many thousands of German colonists

entered the empire, and great numbers of the barbaric tribesmen

took service in the Roman legions, some rising to posts of command.

Germans and Romans also intermarried, and the cultures of the two

peoples were intermingled.

This

peaceful penetration ended with the invasion of Europe by the Asiatic

Huns about 375. The Visigoths {West Goths}, driven from their homes

by the invaders, gained permission from Rome to settle south of

the Danube; then followed in 378 the Battle of Adrianople in which

the refugees defeated and killed the Roman emperor Valens. Later

the Visigoths under Alaric invaded Italy, and in 410 they captured

Rome. Eventually, the Visigoths settled in Spain

and southern France. The Romans

were no longer able to hold back the barbarians, who quickly swept

over the doomed empire. The Vandals wandered into North Africa;

the Burgundians slipped into southeastern Gaul; Angles, Jutes, and

Saxons crossed the sea into Britain; the Ostrogoths {East Goths}

conquered Italy as well as the upper Danube region; the Franks spread

out into northwestern Gaul; and, in 568, the Lombards subjugated

northern Italy.

The Roman Empire

had lived on, after the fall of Rome in 476, with its capital at

Constantinople; but west of the Balkans its territory was occupied

by the several German kingdoms, which were virtually independent.

Eventually these Germans merged with their subject peoples, becoming

Italians, Spaniards, French, and English, and their history became

the history of their new homelands. In general, Roman culture gave

way to German culture, bringing the Dark Ages to Europe. Farming,

trade, political organization, and urban society declined, as a

relatively primitive civilization replaced one that was more advanced.

Even generations removed from barbarian tribal life, and, although

Roman influences did not die, the more backward order prevailed.

Empire

under the Franks: While the other Germans migrated, the

Franks merely expanded from their old homeland into northwestern

Gaul, which they invaded in 481. By 486 the ambitious Frankish chief

Clovis had defeated the Romans in Gaul and had set up his court

in the old city of Paris. The Frankish kingdom expanded in all directions,

conquering the Burgundians, Alemanni, Thuringians, and Bavarians

and ending Visigoth power in southern Gaul. From the time of Clovis

to the Treaty of Verdun in 843 the history of Germany is identical

with that of France.

After

the death in 814, of Charlemagne

his great empire disintegrated. The Treaty of Verdum divided the

empire among the three sons of Louis the Pious, Charlemagne's

son and successor. The western kingdom grew into modern France;

and the middle kingdom, including modern Netherlands, Belgium, Luxemburg,

Alsace-Lorraine, northern Italy, and part of Switzerland, became

a battleground and a buffer state. The eastern kingdom, which developed

into modern Germany, went to Louis the German, the son of Louis

the Pious. Louis reigned until 876 and made some advancement toward

national unity. The son of Louis, Charles the Fat, succeeded for

a time in reuniting the three kingdoms - France, Italy, and

Germany, but as he was unable to defend his empire against the Northmen

the nobles deposed him and elected his nephew, Arnulf, in his stead

{887}.

Roman

Empire and German Feudalism: On the death of Louis the

Child, the last of the Carolingian dynasty {the line of Charlemagne},

the kingship became elective. The first king, Conrad I {911-18},

Duke of Franconia, could neither unite feudal Germany nor defend

it from the attack of the Magyars of Hungary. The most powerful

of the nobles, Henry of Saxony, succeeded Conrad in 919 as Henry

I {the Fowler}, first of the Saxon line and considered to be the

creator of the German Empire; he united the dukedoms under his rule,

built fortresses, reformed the military system, defeated the Hungarians,

and instituted many internal reforms. The royal power was greatly

increased under his son and successor, Otto I {936 -73}, who

was surnamed the Great. Otto restricted the power of the nobles,

making himself complete master in his own kingdom; he defeated the

Hungarians on the Lech in 955; in 961 he acquired the crown of the

Lombards, thus imposing his dominion over Italy; and in 962 he was

crowned emperor in Rome by Pope John XII, thus founding the Holy

Roman Empire, which existed until 1806.

The political

consequences of the intimate union of Church and Sate which was

thus established were unfortunate for Germany; in pursuing the pretension

of world dominion, in attempting to subjugate rebellious Italy,

and in carrying on the long struggle between Church and State, the

emperors dissipated their power and lost control of Germany, which

became increasingly feudal as the other nations of western Europe

became centralized states.

When the Saxon

dynasty became extinct in 1024, the election fell on the Duke of

Franconia, who reigned as Conrad II {1024 - 39}, founding

the Franconian, or Salian, dynasty, which continued in power until

1125. The early monarchs of this line were strong rulers; in Germany

they held their own against the feudal lords, and in Italy they

dominated the Papacy.

Empire

against the Papacy. The struggle between emperor and pope

was base on the papal theory that, since the pope held supremacy

over the Church and the Church held supremacy over the State, all

rulers should be the pope's vassals. The emperor, on the other

hand, maintained that the nobles who elected him conferred his authority

upon him and that he should control Episcopal appointments in his

realm. In 1076 Pope Gregory VII stirred up a revolt in Saxony in

order to break the power of Henry IV {1056 - 1106} and in

1077 he forced the Emperor, in order to preserve his throne, to

present himself as a penitent before the Pope at Canossa. The continuing

State-Church controversy led to renew civil war in Germany, and

Henry himself died a fugitive in his own land. He was succeeded

by his son, Henry V {1106 - 25}, the last king of the Franconian

line.

Finally, during

the reign of Henry V, a compromise settlement of the controversy

was reached in the Concordat of Worms {1122}. This concordat decreed

that henceforth the pope or his legate should have the right to

fill bishops' and abbots' sees in the presence of the

emperor or his representative. The emperor, however, retained the

right to invest a bishop or abbot with the regalia of his office,

and the symbols of temporal authority were to be bestowed before

those of spiritual authority.

Hohenstaufens

and the Holy Roman Empire: When Henry died in 1125, the

papal party prevented the election of Frederick of Swabia of the

House of Hohenstaufen, the nearest heir of the Franconian line,

and the throne went instead to Lothair, Duke of Saxony, who reigned

until 1137 as Lothair II. Frederick and his brother Conrad, nephews

of Henry, revolted, but were put down by the new emperor. Then in

1138 Conrad, Duke of Swabia, ascended the throne as Conrad III and

founded the Hohenstaufen dynasty. Lothair III's son-in-law,

Henry the Proud, of the House of Welf, Duke of both Bavaria and

Saxony, opposed him. Out of their conflict grew the factions known

as the Welfs and the Waiblingers {named after the Hohenstaufen estate

of Waiblingen in Swabia}; the Welfs supported the Papacy in its

struggle with the imperial authority, while the Waiblingers upheld

Conrad in his great struggle with the pope. When the contest was

carried into Italy, the German names of the rival political groups

were corrupted into Guelph and Ghibellines.

Conrad III died

in 1152, after taking part in the Second Crusade, and was succeeded,

on his own recommendation, by his nephew Frederick, Duke of Swabia,

who reigned as Frederick I, or Frederick Barbarossa {Red Beard}.

When Pope Eugene III crowned him in 1155 he added the word "holy"

to the name of the empire, making it the Holy Roman Empire, the

name by which it was thereafter known. His ambition to become another

Augustus in a great empire comprising all Christendom brought him

into bitter conflict with the Papacy and with northern Italy, where

the commercial classes of the rising towns formed the Lombard League

to protect their liberties. Frederick led six expeditions into Italy,

but eventually had to recognize the rights of the Lombard cities.

In Germany he crushed Henry the Lion of the House of Welf and broke

up Henry's great duchies of Saxony and Bavaria. This partition,

intended to weaken the great duchies by dividing them into a number

of petty principalities which would by vassals of the emperor, strengthened

Frederick's position at home, but it had a tragic effect on

the nation: when he perished in the Third Crusade {1190}, Germany

was split up into nearly three hundred principalities, lay and clerical.

Frederick

Barbarossa was succeeded by his son, Henry VI {1190 - 97},

who by marriage and conquest added to his realm the Norman kingdom

comprised of Sicily and southern Italy {called the Kingdom of the

Two Sicilies}. Henry died suddenly, leaving an infant son, Frederick.

Civil war then broke out in Germany between the rival claimants

of the Welfs and the Hohenstaufens. Finally in 1212 the youthful

Frederick {already King of Sicily since 1194} was crowned King of

the Romans; in 1215 he was crowned emperor by Pope Honorius III.

One of the most brilliant and remarkable rulers of the Middle

Ages, Frederick II was little interested in Germany, which he

visited only three times. His primary objective was to unite Italy

and Sicily into a compact state; this ambition brought him into

conflict with the Lombard cities and with the Papacy. Frederick

died in 1250; with the death four years later of his son, Conrad

IV, the imperial line of the Hohenstaufens came to an end.

The

period of the Hohenstaufens is filled with contentions with the

popes and the Italian cities and with constant internal strife.

The royal power became insignificant, and neither German king nor

Roman emperor in reality existed. Some of the rulers seemed little

concerned about Germany, dividing their time between Sicily and

the Crusades, and Frederick II, one

of the ablest of medieval rulers, was not in Germany for fifteen

consecutive years.

The

Rise of the Hapsburgs and its Heritage in Germany: The

period between the death of Conrad IV in 1254 and the election of

Rudolph of Hapsburg in 1273 is known as the Great Interregnum. The

right to choose the emperor had been gradually usurped by a few

of the powerful nobles, who were called electors, and on the extinction

of the Hohenstaufen line these electors practically offered the

crown for sale. Various bidders appeared, and the two offering the

largest bribes, Richard of Cornwall and Alfonso of Castile, were

elected, but neither of them was crowned emperor at Rome or acquired

any real power.

Finally, in

1272, Pope Gregory X ordered a new election, and in the following

year Rudolph I {1273 - 1291}, of the House of Hapsburg, was

raised to the throne. He in a measure restored order and strengthened

the royal authority. Through his defeat of Otttokar II of Bohemia

he acquired lands in southeastern Germany. The most important of

these was Austria, which his son Albert received with the title

of duke; and from this time dates the rise of Austria and the House

of Hapsburg.

During

the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries the intellectual forces

of the Renaissance were beginning

to be felt in Germany, notably in the invention of movable type

by Gutenberg at Mainz {about 1454}. However, there was but little

of interest in the history of the country. The imperial crown was

passed around from one house to another and was openly offered to

the highest bidder, the only care of the electors being to choose

a prince not strong enough to endanger their authority. At one time

there were three rival emperors ruling simultaneously. The first

noteworthy event was the promulgation in 1356 by Charles IV {1348

- 1378} of the Golden Bull, which secured to four secular

and three ecclesiastical princes the right of election and defined

their power. Another noteworthy event was the war of the Hussites.

In 1438 Albert

II of Austria was elected emperor, and from this time until the

dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire the crown was regarded as hereditary

in the Hapsburg family, although the electors always made a formal

choice. Frederick III {1440 - 1493}, who succeeded Albert,

was the last German emperor to be crowned by the pope. The greatest

of the early Hapsburg emperors was Maximilian I {1493 - 1519}.

His reign marked a strong tendency toward centralization and the

material growth of imperial authority. Although he restored much

of the former imperial glory, his war with the Swiss Confederacy

in 1499 lost to the empire the last sections from which an independent

Switzerland was formed.

The

Period of Charles V in Germany: Maximilian was succeeded

by his grandson, Charles V {1519 - 1556}. Besides Germany

and Austria, the Hapsburgs now ruled a vast empire that included

Bohemia, Moravia, Hungary, Transylvania, Italy, Sicily, Spain, Alsace,

Lorraine, Burgundy, Luxemburg, and the Low Countries. Charles bestowed

the Austria possessions of the House of Hapsburg on his brother

Ferdinand, who may be said to have founded the monarchy of Austria-Hungary.

In his reign came the sale of papal indulgences in Germany that

touched off the Reformation, under the leadership of Martin Luther.

The German peasants emboldened by the revolutionary mood of the

Reformation, revolted unsuccessfully {1524 - 1525} against

feudal oppression. The Peace of Augsburg {1555}, with which the

struggle between the Catholics and the Protestants was for the time

terminated, granted the Lutheran states the right to establish Protestant

worship.

In 1555 Charles

V abdicated; he assigned Spain and the Netherlands to his son Philip

II and turned over the empire and the Austrian lands to his brother,

Ferdinand I. The Roman Catholics began a counter-reformation during

the reign of Ferdinand {1556 - 1564}. While Matthias {1612

- 1619} was on the throne, his cousin Ferdinand was crowned

king of Bohemia in 1617, and the attempt to force the Protestants

of that country to accept him as their ruler led to the outbreak

of the Thirty Years' War {1618 - 1648}. The struggle

closed in the reign of Ferdinand III, by the Peace of Westphalia.

Germany by this treaty was divided into over two hundred independent

states, which owed only a nominal support to the emperor and became

in fact simply petty monarchies. The imperial authority was completely

wrecked and never afterward recovered. The war had devastated and

impoverished Germany beyond measure, national feeling had been crushed,

and all unity had been destroyed.

Rise

of Prussia: The interest of German history after the Treaty

of Westphalia centers largely in the rise of Prussia. The Great

Elector, Frederick William of Brandenburg {1640 - 1688}, gained

increased territory for his state, and by strengthening the royal

authority and forming a standing army brought Prussia rapidly forward.

His son, Frederick III {1688 - 1688}, added to his title of

elector of Brandenburg, that of King of Prussia in 1701. Normally

the King of Prussia was still subject to the emperor, but from this

time on, the emperors were in fact merely rulers of Austria, and

the imperial dignity was an empty honor. With the death of Charles

VI {1711 - 1740}, the male Hapsburg line became extinct. The

attempt of Charles by the Pragmatic Sanction to secure his dominions

to his daughter Maria Theresa brought on the War of the Austrian

Succession.

After a two

years' interregnum, the electors chose Charles Vii of Bavaria

as emperor {1742 - 1745}, and on his death Maria Theresa's

husband, Francis I {1745 - 1765}, was elected. His successor,

Joseph II {1765 - 1790}, tried to establish the imperial authority

in southern Germany, but was prevented by Prussia. In 1756 war broke

out between Maria Theresa and Frederick the Great of Prussia {1740

- 1786}. The advantage was decidedly with Frederick, and under

this great ruler, whose statesmanship was as remarkable as his generalship;

Prussia became the equal of Austria and showed itself as the one

possible center for a united Germany. The French Revolution destroyed

the remnant of the empire, and after the formation by a number of

German states in 1806 of the Confederation of the Rhine, under the

protectorate of Napoleon, Francis II formally resigned the imperial

crown and the Holy Roman Empire ceased to exist.

Confederation:

Napoleon's plan to add Germany, or at least the states of

the Confederation, to his empire was frustrated; and at the Congress

of Vienna, which met to restore order out of the chaos into which

European affairs had been plunged, the German states were organized

as a confederation, with the emperor of Austria as president in

1815. The various German states were independent in internal affairs,

and interstate disputes were to be settled by a diet. East state

was to have a constitutional form of government, but this provision

was little observed until the revolutions of 1830 and 1848 forced

the German rulers to accede to the demands of their subjects. In

1830 was formed the Zollverein, which secured free trade among the

several states. In 1848 a national assembly met at Berlin for the

purpose of framing a national constitution, but the rivalry of Austria

and Prussia prevented any successful results, and the Prussian King,

Frederick William IV, refused the title of Emperor of the Germans.

Frederick William

IV was succeeded by William I {1861 - 1888}. The new king

soon styled policy of "blood and iron" made possible

the final firm union of the German nation. The rivalry between Prussia

and Austria was encouraged by Bismarck, who was making ready for

the struggle which he knew would come. The final cause of the outbreak

was the contention over Schleswig-Holstein, which had been taken

from Christian IX of Denmark. War began between Austria and Prussia

in 1866. The outcome was complete success for Prussia, and in 1867

the North German Confederation was formed, with the King of Prussia

as president. The Catholic states of the south, Bavaria, Baden,

and Wurttemberg, held aloof, joining the Confederation just before

the close of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.

The

Germany Empire: By the treaty, which followed the Prussian

victories in the Franco-Prussian War of {1870 - 1871}, France

lost Alsace and Lorraine and was compelled to pay a large indemnity.

The most important result to Germany, however, was the enthusiasm

and the spirit of nationality awakened by the Prussian success.

The German Confederation was charged to the German Empire, and William

I, King of Prussia, was proclaimed German emperor on January 18,

1871. The title, to be hereditary in his family, descended at his

death in 1888 to his son Frederick III. The latter lived but a few

months after his accession and was succeeded by his son, William

II, or Kaiser Wilhelm {1888 - 1818}. William at once showed

his intention to keep personal control of the government and accordingly

in 1890 dismissed Bismarck, who did not approve of his policy.

About 1883 Bismarck

had aided in the formation of the Triple Alliance, which included

Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. Caprivi, his successor, renewed

this in 1891. Under the chancellorship of Hohenlohe, who succeeded

Caprivi in 1894, rapid progress was made in the extension of German

dominion in Africa. Toward the close of the century, Germany acquired

Northeast New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the Caroline,

Palau, and Marshall islands in the Pacific, and shared the Mariana

and Samoa islands with the United States. The murder in 1897 of

two German missionaries in China gave Germany a pretext for demanding

the cession of the port of Kiaochow in Shantung, China; and the

murder of the German ambassador in Peking in 1900 compelled Germany

to take a prominent part in the expedition of the European powers

against China. In 1905 and again in 1911 William II deliberately

provoked the French in Morocco, but each time Great Britain supported

the French position, and the Emperor was obliged to withdraw.

Meanwhile

Germany had strengthened its army and built up a navy that rivaled

that of England. This aggressiveness

alarmed the major powers, and in 1907 Great Britain, France, and

Russia banded together as the Triple Entente. But the Kaiser, as

the German emperor had been called since 1871, countered the move

by reaching agreements with Bulgaria and Turkey; the bonds uniting

Germany with Austria-Hungary and Italy held until Italy's

withdrawal in 1915.

Read more about

Germany and its German Heritage in World War I and later, by looking

up Germany and World War I.

Of

course much has changed since then and the nation of Germany is

a thriving country proud of its heritage. Germany is a place that

you would be proud to display your German genealogy, family coat

of arms or surname history.