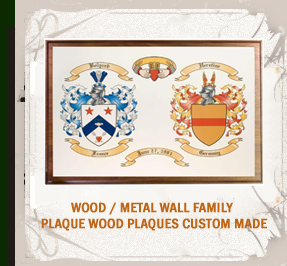

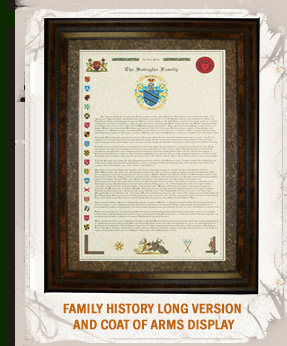

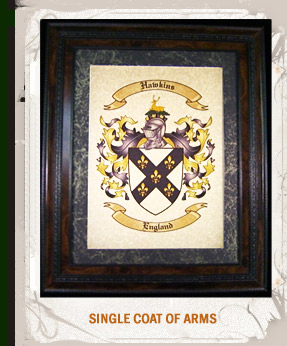

Display Your Family History and Coat of Arms

The

History of the Crusades: The Crusades of the

Middle

Ages were an almost continuous series of military-religious

expeditions made by European Christians in the hope of wresting

the Holy Land from the infidel Turks. From 1096 until nearly 1300,

Crusaders, traveling in great armies, small bands, or alone, journeyed

into the Orient to wage war against the Moslems, who had become

a serious threat to Christianity. Although many went for worldly

gain, it was religious faith that inspired thousands upon thousands

of these "soldiers of the Cross." When the Crusades

began, Europeans were still living in the so-called Dark Ages; before

they were ended, the West stood upon the threshold of the modern

era. The Crusades were not wholly responsible for his progress,

but none will deny that they hastened the development of our modern

world.

How the Crusades Began: The Christians of Europe

believed that pilgrimages to the Holy Land would guarantee the forgiveness

of their sins and the healing of their sick bodies and souls. From

the early 600's Jerusalem was held by the non-Christian Arabs,

but for many years their possession of the city had disturbed the

Christians little or none. Although Jerusalem was a hallowed shrine

from them and for all other Moslems, as well as for Christians and

Jews, the Arabs had not only let the pilgrims come and go at will

but had also permitted Christians to settle and live peacefully

in the Holy Land.

By 1071, when

the Seljuks, a less civilized and less tolerant tribe of Turks,

captured the Holy City, the situation had changed. Soon the Sacred

Places were being desecrated and destroyed; Christian settlers ere

mistreated; and pilgrims were persecuted. In the same period the

Turks threatened to overwhelm the entire Byzantine Empire and then

drive all Christians out of the East. Alexius the Byzantine Emperor,

appealed to the Pope at Rome for aid. At a church council held at

Clermont in southeastern France in November, 1095, Pope Urban II

called upon the faithful to "take up the cross" in Christ's

behalf, rescue Christ's Sepulcher from the infidels, and save

the Christian Byzantine Empire.

Urban's

historic speech set in motion the whole crusading movement. Fired

with religious fervor, people of all ranks clamored to join in the

righteous cause that God had willed. A cross of red cloth worn upon

the breast became the symbol of the departing Crusader {a word derived

from the Latin crux, meaning cross}.

The First Crusade {1096 - 1099}

The

People's, or Peasants', Crusade: By the spring

of 1096, before the First Crusade was officially launched, Peter

the Hermit and other wandering preachers had collected a number

of motley armies, composed of peasants, vagrants, beggars, women,

and children. Driven by fanatical zeal, these ignorant, disorderly,

penniless crews set out from France and the Rhineland for the Holy

Land - more then two thousand miles away. Three of the mobs

were destroyed or scattered in Hungary, in payment for their lootings,

murders, and other outrages; but in July a group led by Walter the

Penniless, a poor knight, and another led by peter the Hermit finally

joined forces in Constantinople forming the first Crusade.

After causing

grave disturbances in the Byzantine capital, the peasants who had

survived the terrible march across Europe pushed on into Asia Minor,

where the Turks massacred them. Peter the Hermit, who remained in

Constantinople at this time, was one of the few members of the People's

Crusade who lived to reach the heart of the Holy Land.

The Princes' Crusade: Meantime, European

princes, barons, and knights had been assembling and setting forth.

From the spring of 1096 through the spring of 1097 they traveled

by land and by sea toward their goal. Major groups included the

French and German volunteers under Godfrey of Bouillon, Duke of

Lorraine, and his brother Baldwin; Frenchmen under Raymond, Count

of Toulouse, and Bishop Adhemar, the Pope's legate; and Frenchmen

and Normans under Bohemund and Tancred. These and other armies make

up of wealthy nobles, humble monks, professional warriors, merchants,

farm hands, vagabonds, and criminals, followed various routes to

reach the common destination. And their purposes also varied. Most

were inspired by religious faith, but many sought adventure, opportunity,

power, or wealth.

The Crusaders

began crossing over into Asia Minor in May 1097, and after a long

and harrowing March, spent the winter outside mighty Antioch. In

June 1098, they captured the city, only to be besieged in their

turn by a powerful Turkish army. Death and desertions sapped the

strength of the Crusaders, and their morale collapsed; but the discovery

of a spear, which they believed to be the one used to wound the

crucified Christ, inspired them to rise up and overthrow the Turks.

On July 15, 1099 after six weeks of siege, the weak remnants of

the Christian armies captured the Holy City of Jerusalem. Covered

with the blood of massacred Turks, the victors knelt at the Holy

Sepulcher, thus bringing to successful conclusion the only crusade

to be motivated principally by religious zeal.

After the death

of Godfrey of Bouillon, who was made ruler of Jerusalem and named

"Advocate of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher", the

Kingdom of Jerusalem was established with Baldwin as its monarch

in 1100. To the north other European princes set up the Christian

states of Edessa, Tripoli, and Antioch. Many Europeans were attracted

to the East, and three religious-military orders - the Knights

of St. John {Hospitalers}, the Knights Templar, and the Teutonic

Knights - were formed to defend and care for the pilgrims

who streamed into the Holy Land.

The Second Crusade and Third Crusade

The

Second Crusade {1147 - 1149}: Stirred by the new

that the Christian County of Edessa had fallen to the Moslems, the

French monk St. Bernard of Chairvaux called for another great expedition

to the East. Louis VII, King of France,

and Conrad III, the German Emperor, led this crusade, which was

to poorly manage that nothing was accomplished. Nevertheless, thousands

of Crusaders, traveling singly or in small bands, continued moving

into Asia Minor.

The Third Crusade {1189 - 1191}: In 1187 the great

Moslem leader Saladin captured the Holy City with a huge Turkish

army. When this news reached Europe, the Third Crusade got under

way. Its leaders were the most powerful rulers of the West: the

German Emperor Frederick I, called "Barbarossa" {Red

Beard}; Philip Augustus, King of France; and King Richard the Lion-Hearted

of England. Although it was

the most famous and colorful of all the military expeditions into

the East, this Crusade, too, ended in failure.

While the German

army was crossing a river in Asia Minor, after the long overland

march from the west, the aged Frederick was drowned. Leopold of

Austria took his place. The English and French Crusaders reached

the Holy Land by ship and liberated the Christian city of Acre {July

1191}, which the Turks had been besieging for almost two years.

Then Richard quarreled with his hated French rival, and Philip returned

to France. Although he was unable to recapture the Holy City, Richard,

the only one of the three kings to continue the campaign, finally

obtained a three year treaty in which Saladin agreed to permit Christians

to visit the Holy Sepulcher without being disturbed. Christian control

over the eastern shores of the Mediterranean was maintained.

Thirteenth-Century Crusades

The

Fourth Crusade {1202 - 1204}: Called the arms by

Pope Innocent III, the warriors of the Fourth Crusade determined

to attack the Moslems in the Holy Land from Egypt. To reach Egypt,

they needed the assistance of the ship-owners of Venice, and to

obtain this assistance they had to help the Venetians crush Zara,

a commercial rival of Venice on the Adriatic, and pillage Constantinople.

The protests of the Pope failed to halt their attacks on these two

Christian cities. As a result of the conquest of Constantinople

in April 1204, the Byzantine Empire fell to the "Latins",

who held it fro more than half a century. The victories of the Fourth

Crusade were purely commercial and political; the situation in the

Holy Land remained unchanged.

The

Children's Crusade {1212}: This tragic expedition

was made by bands of French and German children, who marched to

Mediterranean ports, convinced that the sea would dry up and permit

them to reach the Holy Land. No such miracle occurred, and several

shiploads of the children were carried into slavery in Turkish territories.

The remainder perished, straggled back home, or wandered aimlessly

around Europe. The pathetic story of a band of German children lost

in this terrible crusade may have inspired Robert Browning's

famous poem, "The Pied Piper of Hamelin".

Later Crusades:

Most of the crusades, which followed accomplished little. The Pope

pushed the German Emperor, Frederick II, into leading the Fifth

Crusade {1228 - 1229}. Although Jerusalem passed into Christina

hands as a result of a treaty obtained by Frederick, the Turks recaptured

it in 1244. The Sixth {1248 - 1254} and Seventh {1270} Crusades,

led by the devout Louis IX of France, failed to liberate the Holy

City, which remained in Moslem hands until World War I. The fall

of Acre in 1291 put an end to Christian rule in the Holy Land. A

few Christian traders remained, but the day of the Crusader and

the Western conqueror and settler was past.

Importance of the Crusades

As military

campaigns, the Crusades were a failure, but indirectly, and to some

extent directly, they affected much of the European history that

followed. Numerous important social, cultural, and economic changes

took place during and immediately after these famous expeditions.

While few of these developments can be flatly labeled as results

of the Crusades, almost all were stimulated by the increased interchange

between East and West that the Crusades brought about.

Trade

and Commerce: During and after the Crusades trade between

Italy and the ports at the eastern

end of the Mediterranean were tremendously increased, and wealth

was circulating as never before. By the time European nobility had

begun to look upon such imports as Oriental rugs and perfumes as

essentials, the growing middle class of merchants and craftsmen

was demanding the new foodstuffs, such as cane sugar, rice, garlic,

and lemons, and textiles, such as muslin, silk, and satin, from

the East, which naturally became less expensive as the shipments

increased in size. Natural, too was the growth of towns and cities

in this period. Goods brought into Europe had to be distributed,

and as trade increased, so did the towns and cities along the inland

trade routes. The larger galleys and sailing vessels built to carry

Crusaders were also used to bring luxuries of the Orient to the

courts of England and Scandinavia.

The Crusades

affected finance and business practice in Europe. Gold coins were

minted and letters of credit came into use for the convenience of

the Crusaders. To finance the expeditions, the wealthy were taxed,

and serfs were allowed to buy their freedom and sometimes the land

on which they worked. Thus the number of small landowners was increased,

and the feudal system was weakened. Western gold was widely distributed

through the purchase of supplies and Oriental wares.

Social Change and Intellectual Growth

Growth

from the Crusades: In weakening the feudal system, the

Crusades stimulated the development of a new class of free farmers

and townsmen. In some parts of Europe wealthy "merchant princes"

arose to take the place of the many nobles who were killed in the

Crusades or who settled permanently in the East; in France the monarchy

was greatly strengthened by the waning of the nobles' power.

Contact with

the East and new contacts among the various peoples of Europe led

to the exchange of ideas, customs, and techniques. Thus the Crusades

helped to break down the barriers of ignorance and isolation. During

this period, interest in geography and navigation was tremendously

stimulated; better maps were drawn; and more and more sea captains

adopted the Arabs' crude mariner's compass and astrolabe.

Equipped with new knowledge and urged on by their desire for the

fabled riches of the Orient, European navigators continued to seek

better routes to the Far East until finally they not only sailed

around Africa but also discovered the New World.

The Crusades

encouraged Europeans to attempt to grow the crops and manufacture

the products introduced from the East. The Eastern windmill and

irrigation ditch became common in parts of the Continent. Often

Eastern artists and craftsmen were imported to decorate the great

double-walled stone castles, based on Eastern models, which the

nobles of Europe erected. Native artisans learned from these innovations.

New military tactics and equipment, as well as chivalric traditions

involving heraldry and tournaments, were introduced from the East.

Western writers adapted many Oriental stories, and quantities of

history, fiction, and combinations of the two gave the Crusades

a permanent place in European literature. Popular ballads about

the great expeditions provided the illiterate masses of Europe with

both pleasure and information.

Good

and Evil from the Crusades: The Crusades played a prominent

part in the exciting developments, which occurred in this period,

although they were usually a cause, rather than the cause, of change.

The developments were both beneficial and harmful. The Church gained

great wealth. But wealth brought worldliness; the use of violence

for a religious end and the association of religion with political

and economic aggression troubled many thinking men; and the teachings

of Byzantine philosophers weakened the faith of many Crusaders,

some of whom became Moslems.

During the Crusades,

Europeans came into contact with a civilization, which was, in many

ways, more advanced than their own. Yet many brought back from the

East nothing more than a taste for luxury. Despite the example of

humane tolerance set by such an Eastern leader as Saladin, European

warriors frequently returned from the Crusades to lead campaigns

of violent persecution against religious minority groups. Thus the

aftereffects of the Crusades, like the Crusades themselves, were

a mixture of good and evil.

If

you wish to show the history of your family genealogy by displaying

your family tree and coat of arms, then feel free to visit our website

at The Tree Maker.